"The Udaipur Files" Stay: Legal Analysis of Prior Restraint and Free Speech in India

- Anirud C

- Jul 19

- 13 min read

I. Background and Factual Matrix

"The Udaipur Files: Kanhaiya Lal Tailor Murder" is a controversial film that depicts the brutal murder of tailor Kanhaiya Lal in Udaipur, Rajasthan, in June 2022. The film, starring Vijay Raaz, received CBFC certification but faced immediate film censorship challenges upon its scheduled release on July 11, 2025.

On July 10, 2025, the Delhi High Court stayed the film's release following a petition by Jamiat Ulema-i-Hind and other petitioners, including one of the accused in the ongoing murder case. The petitioners argued that the film contained "visceral hate" and had the potential to inflame communal tensions. Significantly, the accused petitioner raised the additional argument that the film's release would prejudice the ongoing trial and violate the right to a fair trial under Article 21.

The Delhi High Court's order was primarily procedural in nature, directing the petitioners to pursue the statutory remedy available under Section 6 of the Cinematograph Act, 1952—a revision plea to the Central Government. Rather than making a final judgment on the film's content, the court was relegating the matter to the executive branch's revisional authority. Subsequently, the film's producers approached the Supreme Court, which has directed the Centre to "immediately" decide on the revision pleas under Section 6.

This case represents a significant challenge to freedom of expression in India and raises critical questions about judicial overreach in media law. However, it also introduces a complex constitutional dimension: the potential conflict between Article 19 (freedom of speech) and Article 21 (right to life and fair trial). The Delhi High Court censorship stay has broader implications for film censorship in India and the authority of the Central Board of Film Certification (CBFC).

1.1 The Section 6 Revisional Mechanism

To understand the current legal position, it's crucial to examine Section 6 of the Cinematograph Act, 1952, which provides the Central Government with revisional authority over CBFC decisions. Under Section 6, the Central Government can:

Examine any film after certification upon receiving a revision petition

Reverse, modify, or confirm the CBFC's decision

Direct modifications or impose additional conditions for exhibition

This revisional power is exercised by a government committee and represents the final administrative remedy before judicial review. The Delhi High Court's direction to pursue Section 6 remedies reflects the court's recognition of this statutory framework, though the interim stay pending such revision raises constitutional concerns about prior restraint.

II. Legal Justification of the Stay Order

2.1 Procedural vs. Substantive Analysis of the Delhi High Court Order

The Delhi High Court's order must be understood in its proper procedural context. Rather than making a substantive determination about the film's content or constitutional validity, the court primarily directed the petitioners to exhaust the statutory remedy available under Section 6 of the Cinematograph Act, 1952. This procedural approach reflects judicial deference to the executive's revisional authority while maintaining an interim stay pending the government's decision.

However, this procedural stance raises important questions about the appropriateness of interim relief that effectively amounts to prior restraint. The court's decision to stay the film's release while directing statutory remedies creates a situation where constitutional rights are suspended pending administrative action, which may itself violate established principles of constitutional law.

2.2 Constitutional Framework for Prior Restraint

The stay order raises fundamental questions about the constitutional validity of prior restraint on expression. The Supreme Court in Romesh Thappar v. State of Madras, AIR 1950 SC 124 established that prior restraint is the most serious form of restriction on freedom of speech and expression, requiring exceptional justification.

The Delhi High Court's interim stay appears to be based on the "clear and present danger" test, invoking concerns about communal harmony and public order. However, this approach must be scrutinized against the established constitutional benchmarks for prior restraint under Article 19 freedom of expression cases.

2.3 The CBFC Certification and Section 6 Framework

The film had already received CBFC certification, which under the Cinematograph Act, 1952, and the K.A. Abbas v. Union of India, AIR 1971 SC 481 framework, should ordinarily permit exhibition. The Supreme Court in Abbas categorically stated that "freedom of speech and expression includes freedom of propagation of ideas, and that freedom is ensured by the freedom of circulation."

The High Court's direction to pursue Section 6 remedies reflects the statutory framework that provides the Central Government with revisional authority over CBFC decisions. However, the interim stay pending such revision effectively creates a dual-layer censorship mechanism, which may violate the settled principle that once certified, a film acquires the right to exhibition subject only to specific statutory exceptions. This raises serious concerns about CBFC legal challenges and the finality of certification decisions.

The Section 6 revisional process involves a government committee examining the film and the objections raised, with the power to reverse, modify, or confirm the CBFC's decision. While this provides a statutory remedy, the interim stay during this process transforms what should be an administrative review into a de facto prior restraint mechanism.

2.4 Standard of Review for Interim Orders

The legal standard for granting interim injunctions in speech cases was established in S. Rangarajan v. P. Jagjivan Ram, AIR 1989 SC 2117, where the Supreme Court held that "the standards applied for judging the reasonableness of the restriction on the fundamental right of free speech should be applied stringently and without any compromise."

The Delhi High Court's order appears to have been granted without demonstrating an immediate and irreparable harm that would justify such extraordinary relief against certified content. This represents a concerning example of judicial overreach in media law, where courts may be exceeding their constitutional role in content regulation.

III. Constitutional Implications and the Article 19 vs. Article 21 Conflict

3.1 The Emerging Constitutional Tension

While this analysis focuses primarily on freedom of speech and expression under Article 19(1)(a), the case introduces a significant constitutional dimension that the Supreme Court must address: the potential conflict between Article 19 (freedom of speech) and Article 21 (right to life and personal liberty, including the right to a fair trial).

One of the petitioners, who is an accused in the ongoing murder trial, has argued that the film's release would prejudice the trial and violate the right to a fair trial under Article 21. This argument suggests that in specific contexts, Article 21 rights—including the right to a fair trial and personal safety—might outweigh Article 19 expression rights. This creates a complex constitutional balancing act that goes beyond the traditional free speech vs. public order analysis.

3.2 Article 19(1)(a) - Freedom of Speech and Expression

The stay order directly impacts multiple dimensions of Article 19(1)(a) and represents a significant challenge to freedom of speech and expression in India:

Producer's Rights: The filmmakers' right to artistic expression is fundamentally curtailed. In Anuj Upadhyay v. State of U.P., (2021) 3 SCC 172, the Supreme Court emphasized that "artistic expression is a fundamental right" that deserves heightened protection under Article 19 freedom of expression cases.

Audience Rights: The stay also violates the audience's right to receive information and ideas. As established in Bennett Coleman v. Union of India, AIR 1973 SC 106, the right to freedom of speech includes the right to receive information.

Distributors and Exhibitors: The commercial speech rights of distributors and exhibitors are also compromised, creating a chilling effect on the film industry and raising concerns about film censorship in India.

3.3 Article 19(2) - Reasonable Restrictions

The constitutionality of the stay must be evaluated against the permissible restrictions under Article 19(2). The relevant grounds appear to be:

Public Order: The petitioners argue that the film may disturb communal harmony. However, the Supreme Court in Shreya Singhal v. Union of India, (2015) 5 SCC 1 clarified that restrictions on public order grounds must demonstrate a "proximate relationship" between the expression and the anticipated disorder.

Incitement to Offence: The allegation of "visceral hate" must be tested against the "Brandenburg test" adopted in Indian jurisprudence, which requires evidence of imminent lawless action.

Reasonableness Test: The Chintaman Rao v. State of M.P., AIR 1951 SC 118 "reasonableness" standard requires that restrictions be proportionate, necessary, and not arbitrary. The blanket stay without examining the actual content fails this test.

3.4 Article 14 - Equality Before Law

The stay order raises serious Article 14 concerns:

Discriminatory Treatment: Similar films based on communal incidents have been released without such judicial intervention, suggesting potential discriminatory treatment.

Procedural Arbitrariness: The order lacks detailed reasoning and appears to be based on apprehensions rather than concrete evidence of harm.

Classification Issues: The court has not established any rational classification that would justify different treatment for this film.

3.5 Article 21 - Right to Life, Personal Liberty, and Fair Trial

The stay impacts Article 21 rights in several ways, while also being invoked as justification for the restriction:

Artistic Freedom: The Supreme Court in Anuj Upadhyay v. State of U.P., (2021) 3 SCC 172 recognized artistic expression as part of the right to life under Article 21.

Livelihood Rights: The stay affects the livelihood of numerous individuals involved in the film's production and distribution.

Dignitary Rights: The blanket characterization of the film as "hate speech" without proper judicial scrutiny may violate the dignity of the filmmakers.

Right to Fair Trial: Conversely, the accused petitioner argues that the film's release would prejudice the ongoing trial, violating the right to a fair trial under Article 21. This represents a novel application of Article 21 to justify restrictions on Article 19 rights.

Personal Safety: The petitioners also argue that the film's release might endanger the personal safety of individuals connected to the case, invoking Article 21 as a shield against potential harm.

3.6 Balancing Article 19 and Article 21: The Constitutional Dilemma

This case presents a unique constitutional challenge where Article 21 rights are being invoked both to protect and restrict expression. The Supreme Court must determine:

Whether the right to a fair trial can justify prior restraint on certified content

How to balance the accused's Article 21 rights against the filmmakers' Article 19 rights

Whether personal safety concerns can override artistic expression rights

The appropriate standard for such balancing in future cases

The resolution of this conflict will significantly impact Indian constitutional jurisprudence on the hierarchy and interaction between fundamental rights.

IV. Precedential Analysis

4.1 K.A. Abbas v. Union of India (1970)

This landmark judgment established the constitutional framework for film censorship. The Court held that:

Pre-censorship of films is constitutionally permissible but subject to strict standards

The censor board's decision should be based on objective criteria

Courts should not substitute their judgment for the censor board unless the decision is patently unreasonable

The Delhi High Court's order appears to contradict these principles by effectively re-censoring an already certified film.

4.2 S. Rangarajan v. P. Jagjivan Ram (1989)

This case established crucial principles for film exhibition:

A film cannot be banned solely because it may offend some sections of society

The standard for restriction must be "clear and present danger"

Courts must balance free speech rights against public order concerns

The stay order fails to demonstrate the "clear and present danger" required under Rangarajan.

4.3 Shreya Singhal v. Union of India (2015)

This judgment refined the standards for speech restrictions:

Mere possibility of disorder is insufficient; there must be a "proximate relationship"

Speech can be restricted only if it creates "imminent" danger

The "tendency to disturb public order" test was rejected

The stay order appears to rely on the very "tendency" test that Shreya Singhal rejected.

4.4 Amish Devgan v. Union of India (2021)

The Supreme Court emphasized that:

Isolated statements taken out of context cannot form the basis for restriction

The entire context and intent must be examined

Artistic and journalistic expression deserves special protection

The stay order appears to have been granted without examining the film's content in its entirety.

V. Comparative Analysis with Similar Cases

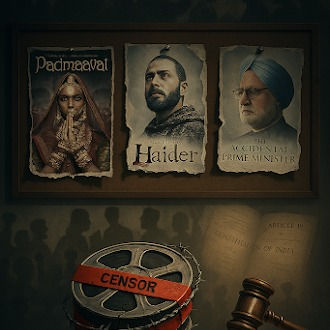

5.1 Padmaavat (2018)

The Supreme Court's handling of the Padmaavat controversy provides a useful comparison. The Court ultimately held that a certified film cannot be banned by states and that artistic expression must be protected even if it causes offense.

5.2 Haider (2014)

Despite controversies over its portrayal of Kashmir, the film was allowed to be released, establishing the principle that complex political subjects can be depicted in films.

5.3 The Accidental Prime Minister (2019)

This film faced similar challenges but was ultimately released, demonstrating that political content, however controversial, deserves protection.

VI. Policy and Societal Implications

6.1 Chilling Effect on Artistic Expression

The stay order creates a dangerous precedent that could significantly impact film censorship in India:

Encourage frivolous litigation against films dealing with sensitive subjects

Make filmmakers self-censor to avoid legal challenges and CBFC legal challenges

Undermine the authority of the Central Board of Film Certification (CBFC)

Create uncertainty in the film industry regarding freedom of expression

6.2 Judicial Overreach in Media Law Concerns

The order raises critical questions about judicial overreach in media law:

The appropriate role of courts in content regulation

The balance between judicial intervention and executive function

The risk of courts becoming de facto censors in Article 19 freedom of expression cases

6.3 Communal Harmony vs. Free Speech

The case highlights the tension between protecting minority sentiments and preserving fundamental rights:

Protecting minority sentiments and maintaining social harmon`y

Preserving the fundamental right to artistic expression under Article 19(1)(a)

Ensuring that the fear of offense does not become a tool for censorship

Balancing public order concerns with freedom of speech and expression in India

6.4 Institutional Concerns

The stay order potentially undermines key institutions governing film censorship in India:

The CBFC's statutory authority and certification process

The finality of certification decisions

The predictability of the legal framework for films

The effectiveness of existing mechanisms for content regulation

VII. Recommendations and Conclusion

7.1 Legal Recommendations

Strict Scrutiny: Courts should apply strict scrutiny to prior restraint orders, requiring compelling state interest and narrow tailoring.

Content-Based Analysis: Stay orders should be based on specific content examination rather than general apprehensions.

Time-Bound Decisions: Any stay should be time-bound with expedited hearings to minimize the impact on expression rights.

Clear Standards: Courts should establish clear, objective standards for when certified films can be stayed.

7.2 Policy Recommendations

CBFC Reform: The certification process should be strengthened to prevent post-certification challenges.

Legislative Clarity: The Cinematograph Act should be amended to provide clearer guidelines on post-certification restrictions.

Alternative Mechanisms: Consider alternative dispute resolution mechanisms for film-related controversies.

7.3 Conclusion

The stay order on "The Udaipur Files" represents a concerning departure from established constitutional principles governing freedom of speech and expression in India. While courts must remain vigilant about protecting communal harmony, this cannot come at the cost of fundamental rights enshrined in Article 19(1)(a).

The order appears to violate the principles established in landmark Article 19 freedom of expression cases like K.A. Abbas v. Union of India, S. Rangarajan v. P. Jagjivan Ram, and Shreya Singhal v. Union of India by:

Imposing prior restraint without adequate justification

Undermining the CBFC's statutory authority and creating CBFC legal challenges

Failing to demonstrate clear and present danger required for restrictions on free speech

Creating a chilling effect on artistic expression and film censorship in India

The Supreme Court's intervention is crucial to restore constitutional balance and ensure that the fear of offense does not become a tool for censorship. This case presents an opportunity to reaffirm the primacy of freedom of expression while establishing clear guidelines for exceptional circumstances where prior restraint may be justified.

The broader implications extend beyond this single film to the very foundations of artistic freedom in India. The resolution of this case will significantly impact how courts balance free speech rights with public order concerns in the digital age, making it a matter of paramount constitutional importance for freedom of speech and expression in India.

This case also highlights the need for reform in film censorship in India, clearer guidelines for CBFC certification, and mechanisms to prevent judicial overreach in media law. The outcome will set important precedents for future Article 19 freedom of expression cases and the scope of prior restraint in Indian constitutional law.

VIII. Intellectual Property Rights Implications

8.1 Copyright Interests

The stay order significantly impacts various intellectual property rights:

Producer's Copyright: Under the Copyright Act, 1957, the film producer holds the copyright in the cinematograph film as a whole. The stay order directly affects the producer's exclusive right to exhibit the film under Section 14(d)(i) of the Copyright Act. This creates a situation where despite holding valid copyright, the producer cannot exercise their exclusive rights due to judicial intervention.

Economic Rights: The stay affects the producer's economic rights including:

Right to commercial exploitation under Section 14(d)(ii)

Right to license exhibition to distributors and exhibitors

Right to sell or assign the copyright

Moral Rights: Under Section 57 of the Copyright Act, the producer (and director) have moral rights including the right to claim authorship and the right to restrain or claim damages for any modification that would prejudice their honor or reputation. The characterization of the film as "hate speech" without proper examination may violate these moral rights.

8.2 Trademark and Personality Rights

Title Protection: The film's title "The Udaipur Files" may have trademark protection or passing off rights. The stay order affects the ability to use and protect this title in commercial exploitation.

Personality Rights: The film depicts real persons (Kanhaiya Lal and his killers). The stay order affects the balance between:

The deceased's family's personality rights

The filmmakers' right to depict matters of public interest

The public's right to receive information about significant events

8.3 Investment and Commercial Rights

Investor Rights: The stay affects the rights of investors who funded the film based on the expectation of CBFC certification leading to exhibition. This raises questions about:

Recovery of investment

Breach of implied warranties about exhibition rights

Force majeure considerations in film financing agreements

Distribution Agreements: The stay impacts various commercial agreements:

Distribution rights acquired by exhibitors

Licensing agreements for music, locations, and other IP elements

Merchandising and ancillary rights

8.4 Precedential Impact on IP Rights

The stay order creates concerning precedents for IP rights in the entertainment industry:

Erosion of Certification Value: If certified content can be stayed without stringent standards, it undermines the commercial value of CBFC certification in IP licensing and investment decisions.

Uncertainty in IP Valuation: The unpredictability of post-certification challenges makes it difficult to value film copyrights and related IP assets.

Chilling Effect on IP Investment: The risk of arbitrary stays may discourage investment in films dealing with sensitive subjects, affecting the overall IP ecosystem.

8.5 International IP Implications

Export Rights: The stay affects the producer's ability to exploit the film internationally, potentially impacting:

Export licensing revenues

International distribution agreements

Cross-border IP licensing

Treaty Obligations: India's obligations under international IP treaties like the Berne Convention require ensuring that copyright holders can exercise their rights effectively. Arbitrary restrictions may conflict with these treaty obligations.

8.6 Remedies for IP Rights Violations

Damages: The producer may claim damages for loss of IP rights exploitation, including:

Lost revenues from theatrical exhibition

Diminished value of copyright due to delayed release

Costs of defending IP rights

Injunctive Relief: The producer may seek injunctive relief to prevent further violations of their IP rights and to ensure expedited resolution of the stay.

Constitutional Remedies: The violation of IP rights may be grounds for seeking constitutional remedies under Articles 300A (right to property) and 19(1)(g) (right to practice profession).

Related Reading and Resources

Key Supreme Court Decisions on Free Speech:

Supreme Court of India Website - Access to full judgments

K.A. Abbas v. Union of India - Landmark film censorship case

S. Rangarajan v. P. Jagjivan Ram - Clear and present danger test

Shreya Singhal v. Union of India - Modern free speech standards

CBFC and Film Regulation:

Central Board of Film Certification - Official certification guidelines

Cinematograph Act, 1952 - Legal framework for film regulation

Constitutional Provisions:

Keywords: film censorship in India, CBFC certification, Article 19 freedom of expression, Delhi High Court censorship stay, judicial overreach in media law, freedom of speech and expression in India, prior restraint, The Udaipur Files legal analysis

This analysis is based on available public information and established legal principles. The final outcome may depend on specific facts and arguments presented before the courts.

Comments